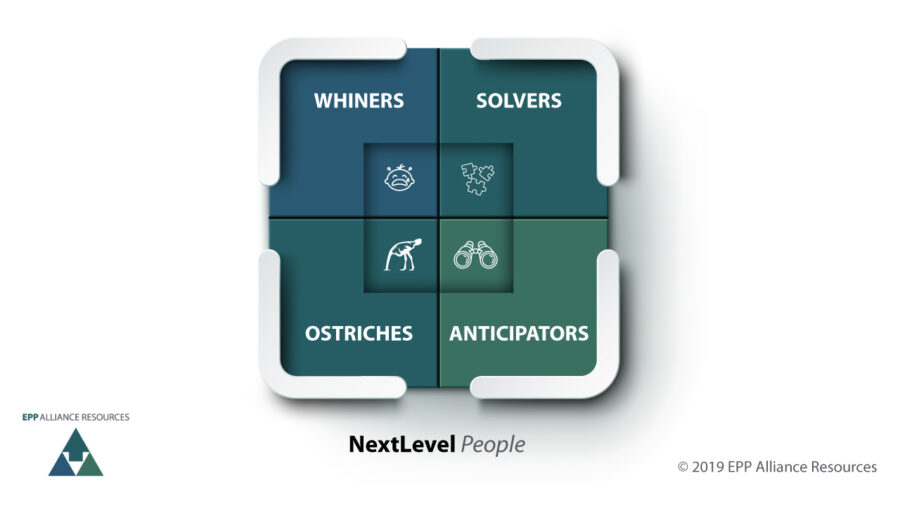

Over the years I have come to recognize that people typically fall into one of four different caricatures. These caricatures almost never fit someone in all situations and at all times. However, each of us most frequently behaves in ways that fit one of these four types, and that shapes how others commonly see us. I have named these caricatures Ostrich, Whiner, Solver, and Anticipator.

First, there are the Ostriches. These people drift through life seemingly oblivious to the problems and opportunities around them. They constantly get surprised by life and find themselves constantly reacting to events around them–often situations they could have avoided or leveraged to their benefit. Other Ostriches, whether out of comfort with the status quo and/or fear of an uncertain future, bury their heads and purposefully resist change. Fortunately, the pain Ostriches repeatedly experience tends to keep people from living in this state for too long, but there are some who repeatedly return to camp here. Avoid Ostriches in your life and business. Their obliviousness can produce collateral damage that harms others close to them.

Second, are the Whiners. These people are the most common. Whining requires no involvement or commitment and seemingly absolves them of accountability. These people love to point out problems but rarely offer solutions or pitch in to help solve the problem. Sadly, these people are often proud of themselves and proclaim that “I just call it as I see it” as some badge of honor. Unfortunately, technology, and therefore our culture often provides the anonymity that emboldens whiners. Get rid of the Whiners in your life and business. They are toxic.

Third, are the Solvers. These people identify solutions to problems and/or willingly get involved in refining or implementing someone else’s idea. They do not get parochial or hog the credit. They just like getting things done that improve their own life and the lives of others. Friends and businesses love Solvers.

Fourth, and final are the Anticipators. These people are rare and exceedingly valuable. These people are able to identify problems or opportunities before others see them coming. They are helpful in avoiding, lessening, or eliminating problems before they adversely impact the individual or group. They can also spot emerging trends before the masses recognize them and gain the advantages that accrue to early-movers. Find these people and watch them closely. They can give you indirect clues to problems around the proverbial corner.

The most powerful combination is a group with a small number of Anticipators (sometimes just one) surrounded by a bunch of Solvers. The Anticipators do not always have the skills necessary to solve or exploit the trends they see. On the flip side, Solvers often cannot see a problem or opportunity until the pain hits. That’s why coupling these two skillsets can give a team huge advantages in the marketplace.